Following yesterday’s review of Tuesday Nights in 1980, here’s Molly Prentiss: Painting a World.

Molly Prentiss was born and raised in Santa Cruz, Calif. She has been a Writer in Residence at Workspace at the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, at the Vermont Studio Center and at the Blue Mountain Center, and she was chosen as an Emerging Writer Fellow by the Aspen Writers Foundation. She holds an MFA in creative writing from the California College of the Arts, and currently lives, writes and walks around in Brooklyn, N.Y. Tuesday Nights in 1980 (Scout Press) is her first novel.

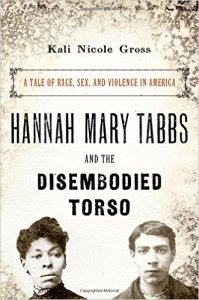

photo: Elizabeth Leitzell

It was mostly done by research. Most of my friends are artists or writers, but not in 1980. I went to graduate school at an art school, so I have been around a lot of visual artists, and my fiancé is a visual artist. Conversations with them often influenced the projects and pieces I referenced throughout my book. I go to a lot of gallery openings in the Lower East Side and SoHo with those friends. But I wouldn’t say I’m an expert of any kind. A lot of it was googling and reading books at the Strand and some trips to the New York Public Library.

What about synesthesia? You portray James’s sensations so vividly.

I don’t have synesthesia, and I don’t know anyone very well who has it. But I do think there are elements of synesthesia that exist within a lot of creative people’s brains. I feel I have really strong associations: with days of the week having a certain color, for example, although I don’t actually see those colors. Words pop into my head when I think of a certain smell or color. I often used my own associations to create James’s. I was enthralled by the idea of synesthesia and I did tons of research on it. I read a particularly great book called Wednesday Is Indigo Blue. It includes charts made by people that have synesthesia, where they describe the exact color of every letter in the alphabet, or they talk about every date on the calendar and what it smells like. They see sparks or flashes before their eyes. They talk about it as if it’s a screen in front of their eyes. They know it’s their synesthesia at work, they know it’s not “real” to the outside world. It was a really fascinating thing to look into, and I especially loved working with language surrounding James’s synesthesia. It’s my favorite way to write, to link one thing to another sort of haphazardly, but also in a way that feels organic.

Your choices of subject and setting are exact and evocative. What brought you to this intersection?

You know, the novel has taken many forms throughout the last seven years. Many of them included much longer time periods, and more characters. An original draft had a very different central character, but then I started writing about his mother, and then I started writing about his mother’s brother, who became Raul Engales, and a lot of that character’s action ended up happening to Raul. But that shifted the timeline backwards a bit, to the late ’70s, early ’80s. And I realized that when I struck on that time period, something started happening. I found I was really interested in lingering there. And the same thing happened with the place setting. In previous drafts, large sections took place in Argentina, and eventually my agent (who I worked closely with to edit the book) and I talked about centralizing it in New York. That was the place where the book really came alive, where the action was really happening, and I could render it the most clearly, because I live here and have had such New York experiences and can speak to that the best. So both of those things happened organically. And the location and the time period ended up becoming central pillars of the book, but I didn’t set off with starting to write a book in the ’80s, specifically. I rooted the book in the characters first and the specific position in time and in place came later.

There was a ton of evolution. James in particular was always a thorn in the side of the book. He used to be a side character. In the beginning he didn’t have synesthesia, and in another version he was going blind. I had to learn how to plot the book, move it forward and give it narrative drive, and I used James for that purpose a lot. He became a central character around which the book really revolves. So there’ve been many shifts in dynamics throughout the book, and ways that the plot and the characters have morphed in order to give the story more heft, or more direction, and those are things that I had to teach myself along the way, how to make the story link up and tighten up and push forward.

In a cast of such weird and interesting people, do you have a favorite, or one you most identify with?

It’s hard. I really like Arlene, who is a side character, but she makes me laugh, just thinking about her. I like her relationship with Raul, which is simultaneously motherly and in some way romantic. I think she’s sort of romantically interested in him. She’s also sort of his mentor, and I like that relationship a lot. I ended up loving James, but he was so hard to write that at some points I really hated him. But in the end he wound up softer, more relatable and kinder than in the beginning.

What were the best and worst parts of those seven years spent writing your first novel?

There were many changes, probably just as many ups as downs, and many exciting parts within the actual writing. There are times when you’re inside of a novel when something clicks, and you can feel it just working, bringing everything into place, and those moments are so thrilling. That’s why you do the rest of the hard work. In terms of pitching the book to agents and selling it and all that, there were some crazy ups and downs. I queried my agent something like two years before I signed with her, and we finally signed and then worked together for three more years, so that was a super-long and arduous process. She was so great, and so helpful, but I would often leave her office in tears because she would have me reworking whole sections, and replotting, and there was a lot of grunt work and overhauls that were really difficult. But on the whole it was really great, to learn how to write the book.

What’s next?

Well, I’m working on my second novel. I’m just in the beginning stages of brainstorming and conceptualizing. The full story is to be determined, but it’s rooted in the way that I grew up, in Northern California in the 1970s, in a community living situation. It will have elements of that, totally fictional of course.

This interview originally ran on February 10, 2016 as a Shelf Awareness special issue. To subscribe, click here, and you’ll receive two issues per week of book reviews and other bookish fun!

Filed under: interviews | Tagged: authors, Maximum Shelf, Shelf Awareness | 1 Comment »