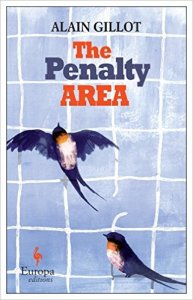

Following yesterday’s review of The Wangs vs. the World, here’s Jade Chang: Method Writer.

Jade Chang has covered arts and culture as a journalist and editor. She is the recipient of a Sundance Fellowship for Arts Journalism, the AIGA/Winterhouse Award for Design Criticism, and the James D. Houston Memorial scholarship from the Squaw Valley Community of Writers. She lives in Los Angeles. The Wangs vs. the World is her debut novel.

photo credit: Teresa Flowers

I never got an MFA, but my college did have a good creative writing program, so I went through writing workshops there. And in workshop, we were always writing short stories. I guess I liked it okay, and when I graduated I continued trying to write short stories, but sometimes a thing is just not your form. And short stories were kind of hard for me. Simultaneously, I was working as a journalist. And I enjoyed writing articles–hated writing on deadline, but enjoyed writing articles. But once I started writing a novel it felt like, ahh!–this makes more sense. Having all this space, all this room, all this time, having a much broader canvas felt more exciting to me. I don’t know that being a journalist affected my experience enormously, except that I think it’s really good training because you learn to not be too precious about your words. I got used to being edited, to rewriting and all that stuff. And that’s good training for any writer.

Did the Wangs come to you fully formed, or did you have to work to build them? Are they based on anyone you know?

There’s definitely no character-by-character corollary for them in real life. I would say that Charles Wang, the father, came to me kind of fully formed. His bluster, his exuberance, his excitement about life, but also his kind-of-asshole side, all of those things felt like–well, like a view of America to me. And then also he just really felt like a lot of fun to do. The other characters definitely felt from the very beginning like real people to me. But I do a lot of character work–I ask myself questions about a character, and a lot of that stuff doesn’t go into the book at all, but it gives me a more well-rounded sense of who someone is and how they will react in a situation that does end up in the book.

Your characters are so rich, and span genders, ages, lifestyles and stages of life.

I knew I wanted to look at contemporary life from several different viewpoints. Growing up kind of between Gen X and Gen Y, I always found that definition of generations really interesting. So I really wanted to have siblings who were in different generations, who looked at the world in different ways. There are roughly 10 years in age between the sisters Saina and Grace, and that’s a huge difference in experience.

Then you have a father who is an immigrant, children born here, and a stepmother who comes from a world that’s actually very different from the father’s, even though to someone who knows nothing about them, you might think that they are from the exact same world. I wanted to show a lot of different viewpoints. And I was interested in getting into a lot of worlds in this book. So you have the father who thinks of himself as a consummate entrepreneur or businessman, who makes a fortune in makeup. And then you have the oldest daughter who is an artist, and so you get to go into the art world. And then you have the middle son who’s a standup comedian and the youngest daughter who is an aspiring style blogger. I really wanted to look at worlds where you have a balance between artifice and reality. It’s all tied to the outset of the financial collapse in 2008, and that particular financial collapse, as most of them are I think, was based on essentially a lie, or the big con–mortgages we couldn’t really afford, and all that. The financial world at that time was falling apart based on a beautiful lie. It made me very interested in other worlds that are based on that as well. I think makeup is definitely that. And then the art world–you know, I love it so much in many ways, but a piece can be worth nothing or millions of dollars, based on who says it is. That is so fascinating to me. I love the overlaps between these worlds, in how we ascribe values to things.

I really enjoyed your shifting perspectives–even the car gets a voice. Was that hard to write?

It was a challenge, and it was a really fun challenge. I definitely knew I wanted to do that. I was joking with a friend that, just like a method actor, I’m a method writer. I just really need to completely be in someone’s head and looking through their eyes in order to fully embody a character. And I liked the challenge of it, honestly. I wanted to see if I could write from five or six viewpoints.

You chose to leave some untranslated Chinese dialogue for the (non-Chinese-reading) reader to decipher from context clues. Why?

A lot of the books that we read in America today are from the point of view of white people in America. Or they’re written for what has been the majority audience, which is white people in America. And I feel like on the one hand obviously this book is for everybody, as every book is, but I wanted a different world of people to get to be the insiders. So people who speak Chinese and can understand the Chinese, they get to be the insiders in this book. But I didn’t want to write it in Chinese characters, because I wanted any reader to be able to kind of sound it out and get that experience of what it feels like to eavesdrop in a language that you don’t understand.

But you’re not actually missing out on anything. There might be something a little bit jokey, or a colloquialism that’s in the Chinese that doesn’t come out in the English, but essentially, it’s all there.

Do you have a favorite character?

I feel a lot of sympathy for Andrew. He is the middle brother, he is really trying hard to find his way in the world, he’s so good-hearted, he really just wants the best for everybody. But he’s also a young guy, and so he makes a lot of dumb missteps. And I just love stand-up comedy. I think it’s so fascinating and so fun. You have to be so smart to do it well, and also so emotionally reckless. I feel a lot of sympathy for stand-up comics in general, and so writing him and writing those scenes where he gets up and does stand-up sets, that really made me love him a lot.

But whichever character I was working on emotionally, working on their emotional arc, I felt a lot of love for that character at that point.

What are you working on next?

I am working on another novel. We’ll see what happens.

This interview originally ran on September 7, 2016 as a Shelf Awareness special issue. To subscribe, click here, and you’ll receive two issues per week of book reviews and other bookish fun!

Filed under: interviews | Tagged: authors, Maximum Shelf, Shelf Awareness | Leave a comment »