These stories about Chinese immigrant families range widely in their specifics, but offer a universal attention to love, hope and striving.

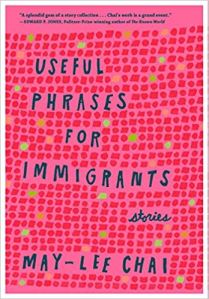

In Useful Phrases for Immigrants, May-lee Chai (Hapa Girl; Tiger Girl) illuminates a range of characters with experiences in common. This story collection is aptly titled: these are tales of Chinese immigrants to North America and, sometimes, within China. They are stories of family and community dynamics.

They encompass an adventure with a dying mother, an ice cream cake that potently stands in for a critical memory of childhood tragedy and the distinctive trials of a Chinese-American traveling to Beijing. A young boy new to the big city quickly learns to play rougher games there. While not linked by specific characters, these stories share certain things: the names and numbers of siblings vary, but details, like a treasured cloisonné bowl, reappear. Such commonalities, rather than contributing to a feeling of homogeneity, lend a feeling of continuity. In other words, families may diverge in their particulars, but face similar challenges concerning culture and relationships.

Literary form varies: one story examines an unfortunate event in public view–a body discovered at a construction site–from the perspectives of five characters, none of whom knew the deceased. Their somewhat clinical approaches leave room for the reader’s compassion to move in. The titular story begins with a simple shopping excursion and gets complicated by the protagonist’s English, which she is still learning. She relies on those useful phrases: “I would like to speak to your manager,” “I know my rights,” “rain check.” The shopping problem turns out to be a stand-in for a larger issue of filial relationships. In the final story, poignantly titled “Shouting Means I Love You,” an aging father makes a pilgrimage to honor his family’s hero; his daughter grumbles before realizing a profound truth.

Chai’s stories carry themes about borders–national, cultural and psychic–and traditions old, new and invented. As the world becomes increasingly global, this material proves ever-relevant. Chai’s prose is often unadorned, but occasionally startlingly lovely: “summer days stretched taffy slow from one Good Humor truck to the next.” Even unnamed characters prove memorable long after their brief appearances.

These evocative stories are variously funny, surprising, gloomy and heartening, ultimately about a universal human experience, of immigration and beyond.

This review originally ran in the September 25, 2018 issue of Shelf Awareness for the Book Trade. To subscribe, click here.

Filed under: book reviews | Tagged: misc fiction, Shelf Awareness, short stories | 1 Comment »