I am a creature, a girl, life stitched from nothing. I am eerie and frightful. And I’m stronger than all of them. I can’t allow any hunter, or Weaver, or betrayal to defeat me. Believing that is all I have. It’s all that might save me.

I have been a fan of Mandanna’s witchy book and this YA trilogy. I’m jumping back in time here to her debut novel, a YA sci fi with some romance elements, naturally enough a coming-of-age story, with some pretty neat philosophical questions. It’s quite good, but she’s gotten better since.

I have been a fan of Mandanna’s witchy book and this YA trilogy. I’m jumping back in time here to her debut novel, a YA sci fi with some romance elements, naturally enough a coming-of-age story, with some pretty neat philosophical questions. It’s quite good, but she’s gotten better since.

Eva is an echo, as opposed to a human: she was not born but made to order by the Weavers for a family who requested her. Echoes are sort of spares: Eva is based on her ‘other,’ or her original, a girl named Amarra who lives in Bangalore. Eva lives in a small English village where she is heavily guarded and tutored and trained in how to be Amarra. She reads what Amarra reads, consumes the same music and movies and foods, wears the same clothes. As far as possible from Bangalore to the English countryside, she is supposed to mimic Amarra, to be prepared to be Amarra if something should happen to the valued human girl. But something has gone awry with Eva: she has a personality of her own. She is not as agreeable as Amarra seems to be. She is strong-willed and stubborn, has interests that different from those of her other. She asks too many questions. Even to have taken a name of her own is a serious crime. [Can I just say how remarkable I find it that she’s taken the same name as in Peter Dickinson’s YA novel that I loved so much?!] And then, of course–this would be necessary for the story’s sake–Amarra dies. And Eva is up for the role of a lifetime, that for which she has been designed.

With obvious parallels to The New One, and a classic we’ll discuss shortly, The Lost Girl examines concepts that humanity has considered before; but that’s certainly not a criticism, nor am I alleging unoriginality. (This book predates The New One, for the record.) Rather, I guess I’m observing that the questions Mandanna is playing with here are of perennial interest. What power do we have to design the people or have the babies we want? Is it appropriate or moral to play with technology that would do so? (There are some efforts at work too in pursuit of immortality, that other perennial human preoccupation.) Eva literalizes the idea of a young person coming of age under the constraints of society or family’s expectations; but on some level every young person wrestles with similar bounds, and necessarily rebels against them. Is Amarra a better girl, or just a different one? Does Eva have a right to self-determination? Many people in their world see Eva as less-than, an abomination. What makes someone human, or a person, or deserving of respect? How do we combat prejudice that’s based on ignorance? How are we to navigate grief? (Hint: maybe not by having a copy of our beloved daughter made to spec, and then demanding she live up to impossible ideals.)

Eva is in a difficult spot. She has to be someone she’s not, both for the sake of her literal survival (echoes are destroyed if they can’t do their jobs) and because she genuinely wishes to comfort Amarra’s bereaved family, who seem like decent people. But she isn’t Amarra. And even dead, the ‘other’ looms large. “Maybe that’s what the dead do. They stay. They linger. Benign and sweet and painful. They don’t need us. They echo all by themselves.”

Mandanna, and the system of echoes, and Eva, are all clear on the reference to Frankenstein here. Echoes are firmly forbidden access to the book, which Eva rightly senses is because there’s something there. Who is the monster–the scientist or his creation? What if you let the Creature set his own path?

Eva’s first-person voice is spot on, the rules of this world are well established for most of the novel, the questions it asks are compelling and thoughtfully explored. The characters are complex and sympathetic, the stakes are high, the whole thing is absorbing. There is a romantic subplot, with tension between Amarra’s boyfriend and Eva’s potential (and obviously highly forbidden) love interest. It’s all really well done, and this novel was headed for a higher rating, but it gets a bit out of control towards the end. The action is a bit unwieldy and the rules of the world collapse a bit, for me, in terms of believability. A certain promise is asked to carry an awful lot of weight in the plot denouement, as if promises are more binding than we know them to be in our world, at least, and indeed it seems to come down to a villain keeping their word, which feels doubtful at best. In an invented world like this, Mandanna could have made a rule of some sort about how promises work–they could have been literally binding–but she didn’t, and the importance of the promise didn’t work for me. I suspect I’m seeing Mandanna’s evolution as an author here, and I’m not mad about it and will still be seeking out her work. My rating of 7 is still solid! But it looked even stronger for a while. I think this author has grown a great deal since her debut.

Great premise, and well done through most of the book; fell off a bit at the end. I am still a fan.

Rating: 7 scones.

Filed under: book reviews | Tagged: children's/YA, romance, sci fi | Leave a comment »

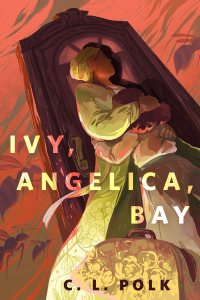

I have been missing Polk’s Kingston Cycle (starting with Witchmark), and was pleased to find a few shorts (for free!) on their website. Here are one short story and two novelettes. (The last is offered with two spellings! Apologies if I’ve used the ‘wrong’ one here.)

I have been missing Polk’s Kingston Cycle (starting with Witchmark), and was pleased to find a few shorts (for free!) on their website. Here are one short story and two novelettes. (The last is offered with two spellings! Apologies if I’ve used the ‘wrong’ one here.)  I was even better pleased to find Theresa again, grown up, in Ivy, Angelica, Bay. The heartbreak hits a bit harder here, perhaps because we are growing up. But she’s coming into her powers, as well. The ending offers a twist I love, with opportunities; I wonder if we might hope for more fiction, perhaps at novel-length, in this world: Theresa and the other mistresses of the bees who come before and after, and the world of good people but also darkness in which they move.

I was even better pleased to find Theresa again, grown up, in Ivy, Angelica, Bay. The heartbreak hits a bit harder here, perhaps because we are growing up. But she’s coming into her powers, as well. The ending offers a twist I love, with opportunities; I wonder if we might hope for more fiction, perhaps at novel-length, in this world: Theresa and the other mistresses of the bees who come before and after, and the world of good people but also darkness in which they move.