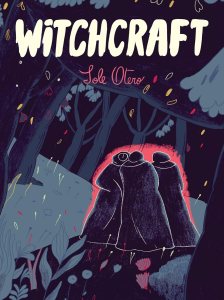

This graphic novel follows an unusual household over several centuries in Buenos Aires, Argentina, through various characters whose lives are impacted, if not ruined, by three enigmatic sisters.

Argentinean comics artist Sole Otero (Mothballs) offers a tale that meanders through historical and speculative fiction with Witchcraft, a graphic novel that spans centuries in Buenos Aires. In Otero’s evolving but recognizable visual style, the opening scene emerges spookily from the fog, as a ship arrives in Nuestra Señora del Buen Ayre in 1768. (One of a series of footnotes explains that this was the original name of Buenos Aires, given by the conqueror Pedro de Mendoza.) Readers see three women disembark with their goat, taking with them the three-year-old son of another passenger, to the latter’s wails of despair. From these early, atmospheric pages, a sense of unease is established and maintained.

The following sections of the narrative undertake large jumps in time. In more or less present-day Buenos Aires, a man tells his friend a scarcely credible story of nude women dancing around entranced nude men, with a goat and a chalk circle and “this super creepy music.” In an earlier, historical setting, a Mapuche woman goes to work at a grand estate for three sisters who are both feared and respected in their local village, to a horrifying end. In modern times, a reclusive woman exchanges e-mails with a similarly lonely man, the veterinarian who came on a house call to look at her sick cat; he tells strange, disturbing tales about his family and the elderly goat they want him to save. A nunnery sends an allegedly evil orphan girl to live with three sisters who normally adopt only boys. From these and other narrative threads, populated by spirits, witch hunts, pleas and losses, readers begin to piece together the fractured story of the María sisters and their unusual, perhaps supernatural, habits.

Otero’s style of illustration varies somewhat between sections, but is often distorted or off-kilter, and highly detailed; in full color, her characters’ facial expressions and contortions advance the unnerving atmosphere of the larger story. Page spreads may include carefully spaced panels or no panels at all; text style likewise shifts, with infrequent footnotes to help readers along. This results in a sinister, mysterious, and deeply compelling reading experience. Translated by Andrea Rosenberg (who also translated Otero’s Mothballs), Witchcraft blends horror, dark magic and dark humor, rage and righteousness. This disjointed, sometimes discomfiting, entertaining story addresses colonial power and indigenous resistance alongside ritual, sex, and sacrifice in an eerie, phantasmagoric package not soon forgotten.

This review originally ran in the August 18, 2025 issue of Shelf Awareness for the Book Trade. To subscribe, click here.

Filed under: book reviews | Tagged: graphic works, historical fiction, horror, in translation, Shelf Awareness, speculative fiction | Leave a comment »