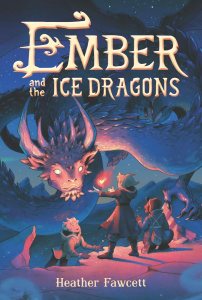

I just went ahead and followed Ember and the Ice Dragons with another Fawcett book for younger readers. This one is a bit darker than that; I see that Ember is catagorized as middle-grade where this one is young adult, for what that’s worth.

I just went ahead and followed Ember and the Ice Dragons with another Fawcett book for younger readers. This one is a bit darker than that; I see that Ember is catagorized as middle-grade where this one is young adult, for what that’s worth.

Even the Darkest Stars is set in a magical-world version of the Himalayas, with yaks and butter tea and very high, very cold mountain climbing. But a parallel world to our own, in which an emperor rules over a huge region, keeping everyone safe from the witches of a bygone time. Our protagonist is Kamzin, a teenaged girl in the village of Azmiri, which is far from the emperor’s Three Cities. Her father is the village Elder; her mother was a great explorer in service to the emperor, but she’s been dead for years. Her older sister Lusha will be the next Elder. She studies astrology. As the younger daughter, Kamzin’s fate is to be the village’s next shaman. She is apprenticed to the current shaman, but is a poor student. Instead, Kamzin has always felt a strong pull to travel, to climb, to run, to map, to explore. When the emperor’s Royal Explorer, the famous River Shara, comes to the backwater of Azmiri, Kamzin knows she must stop at nothing to become a part of whatever has brought him here.

And after some brief intrigue and machinations, we wind up with a race. Lusha, the obnoxious older sister, takes to the road with one of River’s own retinue, aiming to beat the Royal Explorer himself to the top of Raksha – the highest mountain in the world, never climbed by a human, which defeated even Kamzin and Lusha’s late mother. Kamzin succeeds in joining up with the great River Shara, a handsome young man – younger than she’d expected – whom she finds bewitching. Also in their small party is Kamzin’s best friend, Tem, a far more accomplished (though untrained) shaman. And a stowaway: Kamzin’s familiar is a fox (or foxlike critter) named Ragtooth. They share a close bond but also he is apt to bite her. Oh and there are dragons: they are more tangential here than in the last book, but your standard ‘house dragon’ will eat just about anything remotely edible and in response, their bellies put out light. So an alternative to a lantern is to feed your scraps to a dragon. Part pet, part appliance, sometimes a nuisance. It’s quite fun. There’s a lot that is fun in this imaginative world… but also, Kamzin’s world and everyone she loves is in grave danger. It takes a while for the true nature of River’s quest to Raksha to be revealed, but once it is, the stakes couldn’t be higher.

This is a compelling story, populated by mystery, magic, fun creatures, breathtaking landscapes, true friendship, the germ of romance, and a tortured coming-of-age made harder by the possible end of the world. There is also great adventure, death-defying climbs, races for fun and for life-or-death… bit of a Princess Bride list there. My favorite part is that it ends with a clear nod to a sequel, which I’ll have my hands on in a day or so. But yes, also darker than Ember. More bad things happen here, and more is at stake. I may not hand it off to the thirteen-year-old yet. But I am so in for book two.

Filed under: book reviews | Tagged: adventure stories, children's/YA, coming of age, fantasy, Heather Fawcett, romance, witches, young friends | 1 Comment »