Maximum Shelf is the weekly Shelf Awareness feature focusing on an upcoming title we love and believe will be a great handselling opportunity for booksellers everywhere. The features are written by our editors and reviewers and the publisher has helped support the issue.

This review was published by Shelf Awareness on June 10, 2025.

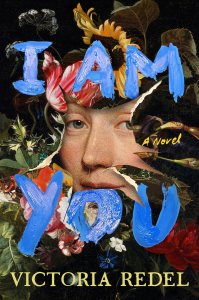

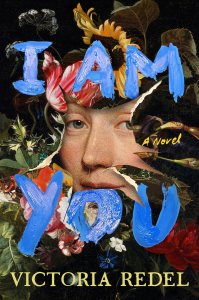

Victoria Redel (Before Everything; The Border of Truth) presents a bold, poignant historical novel about art, love, power, and authorship with I Am You. In the 17th-century Dutch Golden Age of painting, two women with greatly contrasting social and economic status achieve enormous closeness. One is a successful still life painter, the other her maid and assistant. Through their shared story, Redel finds room to muse on art and observation, the wonders of paints and pigments, social strata, interpersonal relationships and power dynamics, gender expressions, and much more. I Am You is no treatise; it is firstly a story of human relationships. But like all great stories, it allows for reflections beyond its literal subjects.

Victoria Redel (Before Everything; The Border of Truth) presents a bold, poignant historical novel about art, love, power, and authorship with I Am You. In the 17th-century Dutch Golden Age of painting, two women with greatly contrasting social and economic status achieve enormous closeness. One is a successful still life painter, the other her maid and assistant. Through their shared story, Redel finds room to muse on art and observation, the wonders of paints and pigments, social strata, interpersonal relationships and power dynamics, gender expressions, and much more. I Am You is no treatise; it is firstly a story of human relationships. But like all great stories, it allows for reflections beyond its literal subjects.

The novel opens in the town of Voorburg in 1653. A child named Gerta is put out to work by her family. Because the household where she is to live needs a boy, Gerta becomes Pieter in service to the wealthy Oosterwijcks. At age seven, Pieter is fascinated by the 14-year-old Maria Oosterwijck: “Her particular words. The varieties of her laughter. The concentration of her fingers as she skimmed or flicked the board with a paintbrush.” Pieter is a quiet child and a hardworking servant, gentle with the rabbits he cares for and butchers for the family meals. Maria, an aspiring painter, is permitted to study only still life, a form considered appropriate for “woman’s art.” She compulsively sketches and paints young Pieter at work: he is “the body most available” to a girl forbidden the study she craves. In his turn, and in his fascination, Pieter begins preparing inks for Maria’s use. He collects the materials–black walnut husks, alder cones, willow bark, oak galls, lichen, marigolds–and crafts them into inks and reed pens. In this way, Maria and Pieter grow up together, intertwined by art and separated by their stations in life. Then Maria, bound for Utrecht to continue her studies, peremptorily declares Pieter a girl once more, in order to to take her as her maid to the larger city.

In Utrecht and then Amsterdam and beyond, Maria and Gerta remain joined. Maria is an increasingly successful painter, commercially and socially, despite the significant impediment of being a woman. Gerta, serving as her maid, becomes progressively indispensable as a talented maker of paints and pigments. Eventually, she teaches herself to sketch and then to paint, becoming Maria’s studio assistant in more functions.

Sometimes Gerta still goes out as Pieter: “How could I erase all I’d known as a boy? Why would I? How much more useful to have known the world both male and female, to traverse brazenly with the rude mind of a boy or angle delicately with a girl’s careful polish.” Her gender-bending is a mode of social expediency, more than of self-identity: “Inside both costumes was me.” In this and other ways, I Am You comments on gender in society, which is only one of Gerta’s disadvantages, but Maria’s chief one. Gerta (or Pieter, as Maria will call her in private all their lives) narrates the novel from start to finish, providing a nuanced perspective on their world, with an evolving appreciation of her limits in it. Even as Gerta’s privileges in Maria’s household expand–she has a nicer bedroom, furnishings, and clothing than any maid should expect–she is reminded that she enjoys these advantages only by Maria’s whim.

Their relationship deepens until the two women become partners in every aspect of life, but Gerta remains subservient. Her devotion to Maria is total, so that even when Maria’s circumstances change and she finds herself ever more dependent on her maid, Gerta is glad to provide a broad range of support. But calamities arise, and there may come a time when the subordinate’s need for recognition, for identity, surfaces. Maria has had a painter’s eye for detail in the visual world from a young age, thanks to both talent and training, but it is Gerta who sees the changing nature of all. “Every day since childhood, hadn’t it been my daily job to make one thing into another? Nut into ink. Stone into viscous paint. The chicken I clucked to as I scattered melon scraps became the stew I spooned into bowls. Even myself, a constant transformation–girl child to boy, servant to budding girl, woman to man to woman, maid to painter to lover….” In the end, it is Gerta who will navigate the hardest choices for the two of them.

Redel excels at sensory and imagistic writing, particularly in the thrilling qualities of color, inks, paints, and pigments, and revelatory art. Her descriptions of the sights, smells, and sounds of daily life, food, and housekeeping are visceral. She writes expressively about sex, which in this novel can be both pleasure and communion, and also disturbing–as an abuse of power, and with questionable consent. The canals of Amsterdam, the butchering of dinner, and the disposal of bodily wastes alongside tender caresses and vivid achievements on the canvas: Redel offers compelling descriptions of both splendor and pain.

I Am You is a novel that deals with heavy themes and tough choices. Gerta’s sensitive, incisive perspective often reveals sad and distressing events, as well as the transcendent revelations of creative work. In considering art, love, gender, and class, her story confronts injustice and tragedy as well as beauty. The result is sensual, thought-provoking, and unforgettable.

Rating: 7 rabbits.

Come back Monday for my interview with Redel.

Filed under: book reviews | Tagged: historical fiction, Maximum Shelf, Shelf Awareness, visual arts | 1 Comment »