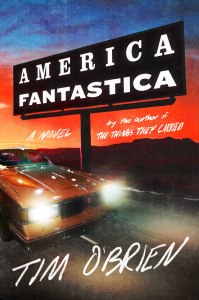

Following Friday’s review of America Fantastica, here’s Tim O’Brien: Route 66 Meets MAGA America.

Tim O’Brien is the author of the novels Going After Cacciato; The Things They Carried; In the Lake of the Woods; and others, as well as memoirs including If I Die in a Combat Zone, Box Me Up and Ship Me Home. He has won the National Book Award for Fiction, the James Fenimore Cooper Prize, and the Katherine Anne Porter Award, and was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Critics Circle Award. O’Brien has been elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. His eighth novel, America Fantastica, a wild ride through a paranoid nation, will be published by Mariner Books on October 24, 2023.

What brought you back to writing a novel after more than 20 years?

Tim O’Brien

(photo: Tad O’Brien)

The character of Angie Bing. She came into my head, I don’t know, 20 years ago, as did the antihero, Boyd. I tried to push them away for a long time. They just kept yapping at me. Put me in a book! Especially Angie. It was that voice inside my head for all those years that convinced me to at least try. And it was fun. I enjoyed her.

I was pretty determined not to ever write another novel. It’s hard work and often frustrating, all the things that go with a 400-something page book. Five years of my life. I was a little reluctant to do it, but once I started, I got a kind of perverse pleasure out of it.

America Fantastica contains so many characters, events, places. How do you stay organized?

The organizational tool is my head. It’s nothing much beyond that. Occasionally I would lose chronology, but then I simply go back and reread and rediscover.

The novel switches voices among many of those characters. How fun or difficult is that?

It was a great pleasure, going from voice to voice. There are some pretty nasty people in the book–most of them, in fact–and it was fun being nasty. I see it around me so much. It was a sort of Jonathan Swift/Mark Twain fun, curmudgeonly. You call a bank or an airline and they’ll have that message on: “Our phone lines are unusually busy; please hold.” They’re not unusually busy. They’re usually busy. In fact, they’re always busy. Things like that were fun to strike back at.

Do you have a favorite character?

No. Characters, probably for all writers, are like your own children. You don’t pick them. They’re very different. I don’t approve of most of the characters in this book, but I don’t approve of most of the people I see on CNN and Fox, either.

This work of fiction is centered on the lying or fictionalizing of its characters.

It’s been a theme that’s gone through my entire work and probably my entire life, going way back even to my childhood. I grew up in a small town and spent a lot of my time in my own head, imagining I was not in this godawful place. That followed me to Vietnam and has followed me through adulthood. It’s astonishing the things that we witness that seem almost impossible, incredible, especially during the Trump years. How can this be happening in a country I really had loved as a kid? It seemed as if I were living in a fairy tale that couldn’t be true, and yet seemed true. And so all of my work has to do with this blend of our imaginations and the realities we see around us. This book probably is the most blunt about it. Boyd seemed to represent for me what I’m witnessing socially, culturally, and politically in this country, a kind of shameless lying or deceit. I wanted to have as a foil someone who was pretty certain about the world–Angie has a kind of religious certainty about the world. The tug of war between them was fascinating.

Angie came first?

They came together. I imagined her originally as a bank teller, and then almost instantly I imagined Boyd as a small-town entrepreneur (later a JCPenney manager), and within 20 minutes or so I had him robbing that bank as the novel begins. Robbing it essentially for entertainment, as a way of making himself move out of his lethargy and do something in the world. When he invited her along, or made her come along, a kind of Route 66 theme dominated, and it stayed throughout the entire book. It’s sort of a Route 66 meets MAGA America kind of book.

I knew it would be set during those years. They were the years that I was living through, with my mouth agape as I watched the television set. It seemed appropriate to have a character who was a shameless liar and had been his entire life, and to find out why. Why do people do this sort of thing? There’s a quote at the beginning of the book by Yeats: “We had fed the heart on fantasies, / The heart’s grown brutal from the fare.” That’s what I saw happening around me, that sort of fantasy: of a lost election being a winning election, for example. I wanted a hero who was part of the conspiracy world, coming up with these bizarre fantasies about the world and apparently believing in them, repeating them enough to believe in them.

By having such a human being as one of the two main characters in the book I felt I was trying to get into what made people do these sorts of things. For my hero, Boyd, it goes back to his childhood, as we learn late in the book. He began, even as a kid, living in a fantasy world as a way of escaping the world he was in. It can have terrible consequences, and did for him: a broken marriage, a lost career. But on the other hand, fantasy keeps us going. The fantasy that tomorrow will be better than today. Maybe fantasy isn’t the word, but the hope or the dream that things will improve for all of us. I’ll win the lottery, I’ll have a great time in Yellowstone, I’ll meet the girl of my dreams or the boy of my dreams. I think we need fantasy. So there’s that tug of war, when what we need can have terrible consequences. That will always fascinate me, and has since I was a kid.

What are you working on next?

I’m working on my golf game.

Nothing. I’d been working on this book all the way through page proofs and so on; it still feels like in my head I’m working on it.

Are you one of those writers who’s never done, even when it’s printed and published?

I am. I’ve made changes in The Things They Carried; In the Lake of the Woods; [Going After] Cacciato. I slip them in when they print a paperback edition. Most of them minor and none of them noticed, except by scholars. I did have a letter from a high school English teacher once who disputed my changes.

This interview originally ran on July 27, 2023 as a Shelf Awareness special issue. To subscribe, click here, and you’ll receive two issues per week of book reviews and other bookish fun.

Filed under: interviews | Tagged: authors, Maximum Shelf, Shelf Awareness | Leave a comment »