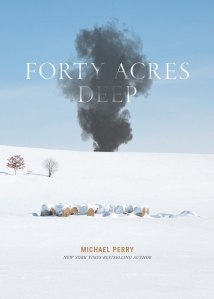

A loan from a dear friend, from one of his favorite authors, and I can see why. This novella-length story was absolutely grim, but often funny, too, and deals with some serious messages. I don’t do this often, but let me give a big **content warning** for suicide.

A loan from a dear friend, from one of his favorite authors, and I can see why. This novella-length story was absolutely grim, but often funny, too, and deals with some serious messages. I don’t do this often, but let me give a big **content warning** for suicide.

It begins:

Harold had come to consider the accumulating weight of snow on the farmhouse roof as his life’s unfinished business. Daily the load grew… on his heart, his head, the creaking eaves.

A few paragraphs later:

She died a month ago, and he hadn’t plowed the driveway since.

That sets the stage pretty well for us, and all on page 1 (no spoilers). Harold has lived on the same farm all his life, inherited from his father, in a vague midwestern setting where they get a lot of snow. They were dairy farmers, but the economics of that lifestyle got increasingly hard, and then the barn burned – with the cattle in it – a trauma as well as a financial blow. He turned to beef cattle, although one hard winter, with he and the wife both down with the flu, he had to send them to market at the worst time of year, and thus got out of that business. He tried cash crops, but the prices dropped out of beans and corn, too. He leased the land to a farmer who never showed up in person; instead he sent “hired-hand agronomists with wands and laptops and satellite-guided monster machines.” There is a definite note of ‘things these days’ and ‘good old days,’ phrases against which Harold – to his own derision a part-time follower of philosopher and poetry – consciously rebels. He is an old, straight, white man, and he notes his own prejudices and old-fashioned attitudes, and actively interrogates them.

“She” was his wife, and when she dies, Harold wraps her in blankets and puts her out on the porch. He can’t bring himself to face the world. Instead he shovels the walk to the chicken coop, cares for the hens and eats their eggs with canned beans, almost his only remaining provision. He runs the kerosene-powered torpedo heaters, pointed up at the pole barns’ roofs, hoping to keep them from collapsing under the weight of the snow. He ruminates, contemplates, checks remembered quotations in his old philosophy texts. We see him visit town just a few times, where he has a minor but meaningful interaction with a barista whose context could hardly be more different from Harold’s. (It doesn’t take much interaction to hold significance for Harold, who mostly speaks only to his chickens, or himself.)

Harold is an interesting character. When he discovered Montaigne as a teenager: “instead of what he expected a French philosopher might write about, he found references to sex and farts. This was silly and appealed mostly to his dumb teen prurience, but it also implied that philosophy might be accessible and relevant even for a horny rube in barn boots.” He is both country farmer and philosophy student, both privileged old white guy and actively interested in the pronouns, the rainbow flag, and the new ways of thinking. He knows he’s not accomplishing anything big here, but I think you’ll join me in respecting his small curiosities.

Perry is a masterful writer. Harold’s story is almost unrelentingly, deeply depressing – that’s hardly a strong enough word. Nothing goes right, everyone he’s ever cared for is dead, there is nothing left to hope for. His story is also extremely funny: Harold possesses a remarkable sense of humor, and Perry renders it in prose that often surprises while commenting (cynically, of course) on the American condition. “Another yoga-panted woman was griping down at him from her Denali over how much he undercharged for digging her prairie restoration patch.” “After sundown the horizon to the west glowed with encroaching fitness center, brewpubs, and mitotic apartment complexes.” Even as the snow-buried landscape obscures, buries, kills, it is beautiful, and so is this book: both story and line-by-line writing. Harold has a hell of a vocabulary, too. He makes fun of himself for knowing how the meaning and spelling of ‘jejune’ but not how to pronounce it (me neither, Harold). Echolalia, misophonia, cotyledon, vermiculite, hyperacusis, exudation, popple whip.

One of Harold’s last backhoe jobs was for a wealthy architect who hired him to rearrange a set of decorative boulders amidst the shrubbery surrounding a cavernous riding stable. Afterward, when they were settling up, Harold said, “Nice pole barn.” He truly intended the compliment. The architect stared at him blankly for a beat, then, as if dictating from behind a lectern, declared, “It is a custom barndominium-slash-hippodrome.” Harold waited for the slow grin that would concede the absurdity of the extravagant jargon, but after an uncomfortable straight-faced silence, the man slipped an iPhone from his velveteen corduroys and said, “Do you accept Apple Pay?” Omnipresent, Harold thought, were the signs that contemporary culture was leaving him the dust. “Nope,” said Harold, and handed the man an invoice scribbled out on a carbon paper slip.

Lest you think this is overly crabby: Harold (and therefore, obviously, Perry) is aware of his own part in this caricature. At an entirely separate set of reflections, “You are being petulant, he thought. And grandiose.” He excels at the unwieldy, surprising, barking-laugh-out-loud list: “the world’s privileged hordes were content to skate along on… the secondhand grease of star-spangled draft-dodgers peddling hot water heaters, bald eagle throw rugs, and resentment.” Etc.

It’s not all this wordy. “At first light every tree branch, every blackberry cane, every stick and stem was a hoarfrost wand. The sky was clear, the air was still, and sunlight splintered every which way.” It can be as clean and smooth as snow-covered fields, where every tool or piece of garbage is softened over into something vague and beautiful.

This is a masterful piece of art. Extremely grim and dour, but beautiful.

Rating: 9 pictures.

Filed under: book reviews | Tagged: family, mental health & illness, misc fiction, nature, novella | 1 Comment »