Maximum Shelf is the weekly Shelf Awareness feature focusing on an upcoming title we love and believe will be a great handselling opportunity for booksellers everywhere. The features are written by our editors and reviewers and the publisher has helped support the issue.

This review was published by Shelf Awareness on July 27, 2023.

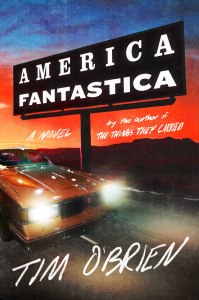

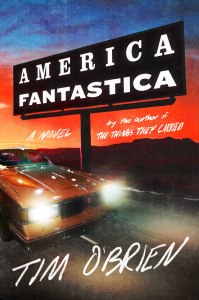

Set against the backdrop of an unnamed but recognizable American presidency, Tim O’Brien’s black comedy, America Fantastica, takes both the dark and the comic to epic proportions with simultaneous absurdism and poignancy. O’Brien (The Things They Carried; If I Die in a Combat Zone, Box Me Up and Ship Me Home) here offers his first novel in more than 20 years–a sprawling, madcap tale of road trips, crimes large and small, love, loss, and, most of all, lying. Like The Things They Carried, America Fantastica revels in detail and highly specific lists, so that the world it portrays feels robust and brimming.

Its opening lines set the tone, far-reaching and grandiose: “The contagion was as old as Africa, older than Babylon, wafting from century to century upon sunlight and moonbeams and the vibrations of wagging tongues. During the second decade of the twenty-first century, the contagion alighted in Fulda, California, riding aboard the bytes of a MacBook Air…. Reinvigorated by repeated utterance, fertilized by outrage, mythomania claimed its earliest victims among chat room patrons–the disappointed, the defeated, the disrespected, and the genetically suspicious…. The disease spread northward into Oregon, eastward into Idaho, arriving on Pennsylvania Avenue in January of 2017.”

Readers first meet O’Brien’s antihero in action. “On an afternoon in late August of the year 2019, after locking up the JCPenney store on South Spruce Street, Boyd Halverson strode out to his car, started the engine, sat without moving for several minutes, then blinked and wiped his eyes and resolved to make changes in his life. He had grown sick and tired of synthetics, rayon in particular.” He departs his Kiwanis brunch early to head to the bank, where he presents a gun and leaves with just under $81,000 and the teller, “a diminutive redhead named Angie Bing.” She is technically kidnapped, but Boyd will repeatedly try and fail to ditch her over the coming months. His name is not really Boyd Halverson and his entire résumé is a fiction. He had in fact been married, had a child, had an impressive career as a foreign correspondent and nearly won a Pulitzer Prize. But that life was built on lies, culminating when “at last he collided with the sudden, brutal, and well-earned catastrophe he’d been patiently anticipating for decades.”

Boyd and Angie hit the road, seeking first Boyd’s ex-wife, Evelyn, and then her father, Dooney, against whom Boyd holds a significant grudge. Their travels prompt movements by an increasingly colorful cast of bizarre characters. Dooney and his partner Calvin flee the possibly murderous Boyd from Port Aransas, Tex., to Bemidji, Minn., and onward. Randy, Angie’s boyfriend, an almost-laughably amoral electrician/rodeo cowboy/burglar, tracks Angie from Santa Rosalía, Mexico, to Santa Monica, Calif., and beyond. Along the way, he meets two ex-cons at a diner in Los Angeles who latch onto his interest in an unreported bank robbery. These characters set the tone of a novel dealing equally in ludicrous comedy, political commentary, and pathos. They will be joined in O’Brien’s imaginative, wide-ranging tale by a violent, egomaniacal CFO; a bank president and his wife, both with a gift and passion for fraud; a racist cop; an Amazonian CrossFit gym owner and amateur detective; a small-town sex worker with either an excellent act or multiple personalities. Events range from disturbing to ridiculous, often simultaneously, as when Boyd gets his toes broken with a monkey wrench by an unlikely pair of sidekicks. These characters and events, in a series of deftly drawn American locales, form a fantasmagoria, a version of reality that both bizarrely exaggerates and digs directly into the emotional truth of the real world.

O’Brien opens with a Yeats epigraph: “We had fed the heart on fantasies,/ The heart’s grown brutal from the fare.” His novel speaks of a nation that craves delusion and deception; O’Brien’s profile of the 2019 United States is savage, blending satire and realism. “Off with their heads! Climatologists? Chemists? Off with their tongues! Who needs reality when you have Venom? Who needs history when you can manufacture your own?” Is it plausible that Boyd, an esteemed investigative journalist, exposed as a liar, might in turn expose larger wrongs than his own?

America Fantastica showcases a broad emotional range, as Boyd Halverson (aka Otis Birdsong, aka Junior, et al.) turns out to harbor some very real trauma amid a fabricated personal history, and at least one complex personal relationship. It is a story chock-full of lies or fictions, a theme O’Brien has explored in earlier works as well. “[Boyd] had fervently believed every word, every unearned moment of an unlived life. Yes, he was a Princeton graduate. Yes, he had distinguished himself in the Hindu Kush, scaled Mount McKinley, survived brain cancer, scored near-perfect on his SATs. But so what? Why risk failure when a fib was always conveniently at hand?” By the novel’s end, readers will have learned–more or less, as far as we can tell–the “real” truth. This feels in some respects like a hopeful conclusion. But the truth itself is more grim than hopeful, which is perhaps the most realistic–truthful–possibility.

As in the earlier works for which he has long been recognized, O’Brien here demonstrates an electric combination of deadpan humor, vicious wit, and a masterful eye for detail in capturing a peculiarly American form of torment.

Rating: 7 wiggles.

Come back Monday for my interview with O’Brien.

Filed under: book reviews | Tagged: absurdism, Maximum Shelf, misc fiction, Shelf Awareness | 1 Comment »