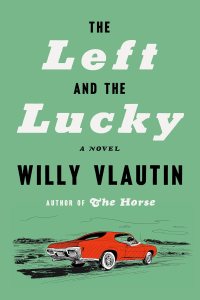

In a gritty world bordering on hopelessness, a man and a boy form a friendship that may just save them both.

Willy Vlautin (The Horse; The Night Always Comes; Don’t Skip Out on Me) applies his characteristic compassion and spare tone to an unlikely friendship in The Left and the Lucky, a novel of hard times and scant hope. A boy whose life has been ruled by abuse and neglect and a man whose hard work has been rewarded by betrayal and loss find each other in working-class Portland, Ore., and forge a hard-won bond to their mutual benefit.

Russell is eight years old and small for his age. He lives with his grandmother, who has dementia; his mother, who works nights; and his teenaged brother, who is angry and troubled. As the latter spins further afield and poses an increasingly serious physical threat, Russell dreams of building a boat or an airplane to take him away to an unpopulated island near Hawai’i: he can think of no nearer salvation.

Eddie lives next door. He runs a small house-painting business, working six or more days a week, and his main employee is a scarcely functioning alcoholic whose paychecks Eddie handles for him with scrupulous honesty. It will take the bulk of the novel for Vlautin to reveal the rest of Eddie’s painful past, gradually filling in the reasons for his generosity. Russell turns up on Eddie’s rounds of the neighborhood: out too late, hiding from something. The man offers the boy food, a ride home. Russell begins waiting in Eddie’s backyard each night after work; he cleans paintbrushes after the workday. Eddie gives him odd jobs and shelter from violence. Each is lacking something in a life lived on the margins, but together they begin to build a slight, meaningful solution. They restore an old Pontiac and care for an old dog. Each finds in the other someone who needs them to survive.

In his eighth novel, Vlautin continues to focus upon an American underclass marked by desperation and poverty, people often forgotten or abandoned. With a gruff tenderness, a quiet lyricism, and moments of humor, he highlights not only the built family that Russell and Eddie assemble, but also motley characters from their neighborhood: Eddie’s employees, an aging aunt, a waitress with goals, Russell’s seething brother. The Left and the Lucky is often grim, but Eddie’s dogged decency uplifts even in this grayscale world of limited options; his unwillingness to give up on Russell offers a slim but profound thread of hope unto the story’s end. Vlautin’s character sketches and the careful value he places on perseverance are not soon forgotten.

This review originally ran in the February 13, 2026 issue of Shelf Awareness for the Book Trade. To subscribe, click here.

Filed under: book reviews | Tagged: family, misc fiction, noir, Shelf Awareness | Leave a comment »