Maximum Shelf is the weekly Shelf Awareness feature focusing on an upcoming title we love and believe will be a great handselling opportunity for booksellers everywhere. The features are written by our editors and reviewers and the publisher has helped support the issue.

This review was published by Shelf Awareness on January 17, 2024.

Yael van der Wouden’s first novel, The Safekeep, explores the rural Dutch landscape in the years following World War II through the life of a lonely, sheltered woman reluctantly forging new bonds. In what is largely a closed-in, personal story with a solitary protagonist, van der Wouden also examines larger issues in the social context of Dutch postwar society.

Yael van der Wouden’s first novel, The Safekeep, explores the rural Dutch landscape in the years following World War II through the life of a lonely, sheltered woman reluctantly forging new bonds. In what is largely a closed-in, personal story with a solitary protagonist, van der Wouden also examines larger issues in the social context of Dutch postwar society.

The story is set in 1961, in a rural Dutch province that has largely recovered from war, on its surface. Isabel has spent her life tucked away in the house where her family relocated from Amsterdam during the war. An uncle found the place for them, and 11-year-old Isabel took up residence with her mother, younger brother Hendrik and elder brother Louis. Eventually, their mother died and the brothers moved away, but Isabel stayed, believing there was nowhere else for her. She keeps the house meticulously, polishing dishes and micromanaging a series of beleaguered maids. “She belonged to the house in the sense that she had nothing else, no other life than the house, but the house, by itself, did not belong to her.” She lunches occasionally with Hendrik, less often with Louis. In her lonely, strictly regimented life, the house is Isabel’s constant, the thing she can control, her greatest comfort.

The Safekeep opens in her garden. While digging out late-season vegetables, Isabel finds a shard of broken ceramic, “Blue flowers along the inch of a rim, the suggestion of a hare’s leg where the crockery had broken. It had once been a plate, which was part of a set–her mother’s favourite…. There was no explanation for the broken piece, for where it had come from and why it had been buried. None of Mother’s plates had ever gone missing.” This beginning offers an early clue that Isabel’s understanding of the house and its contents, of her own personal history, may be flawed.

Further disruptions follow. Hendrik, a steadfast supporter of his solitary sister, nevertheless lives a life she hasn’t come to terms with. He lives with a man; this makes Isabel uncomfortable. Worse, Louis brings yet another young woman, Eva, to a dinner with his siblings. Eva sets Isabel on edge for reasons Isabel does not understand. Additionally, any serious liaison for Louis implies a threat to Isabel, who is permitted to stay in the house only until Louis (its intended inheritor) settles down to start a family. Worse yet, at Louis’s insistence, Eva comes to stay at the house with Isabel while he is on a trip: Isabel is horrified to be made to share her space with a woman she despises.

The tension in the house rises to a nearly unbearable pitch. Isabel habitually suspects her maids of stealing, and now suspects Eva, whose own history is murky, as well. Isabel obsessively inventories china dishes, silverware, and items of décor, counting spoons and watching Eva’s every move. She cleans and displays and relocates the mysterious shard of plate from the garden, imbuing this small object with outsized power. Eva’s presence continues to feel inexplicable. Louis’s return from abroad, to collect Isabel’s unwanted houseguest, is delayed. Tensions continue to build.

Van der Wouden excels in surprises, including changes in tone. The Safekeep remains, almost in its entirety, nearly claustrophobic in its focus on Isabel’s commitment to her family home. “Bound to the house, [Hendrik] said. As if it was a tether and not a shelter. And not her own love, too.” But this tightly bound, insular story of one woman’s struggle finally zooms out, with near dizzying quickness, to engage with larger questions. An old friend of Isabel’s mother is preoccupied with a dish that was given to her “to keep” before the war, by a neighbor who now wants it back. This friend believes it is hers now; the neighbor disagrees. “What does it matter, gifting, keeping? She gave it to me. It was a terrible time. She was gone for years.” As its title hints, van der Wouden’s novel will puzzle over various meanings of safekeeping. Likewise, the sparsely populated story is punctuated by passages of erotic writing that surprise as much by their loveliness as by their departure from the book’s otherwise lonely atmosphere. Not only the story of one family’s struggle or Isabel’s quiet pain, The Safekeep addresses themes of yearning, possession, the difficulties of Dutch recovery from World War II and of same-sex couples’ experiences in a society still regaining its feet.

In the end, like a country recovering from a trauma, Isabel must step outside her space of comfort and familiarity in order to learn and grow. “Isabel tested one [of the frozen canals] with her foot, and found it solid, and then stood on it in wonder: a miracle, she thought, to stand so solidly on what could also engulf you.” Van der Wouden communicates and implies much with a minimalist style that is often quietly, shockingly, beautiful. “The shadows lifted as though they’d only been glimpsed under the hem of a skirt–the lift on an arm, secrets of the body that only unfolded for the night.” The Safekeep is a slow-burning, deceptively austere novel, whose subtle, crafty questions and lovely, lyric style will follow the reader long after its conclusion.

Rating: 8 pears.

Come back Friday for my interview with van der Wouden.

Filed under: book reviews | Tagged: family, historical fiction, LGBTQ, Maximum Shelf, Shelf Awareness | 1 Comment »

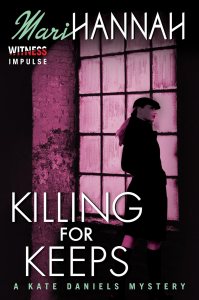

Doing another short-short review of this fifth book in the DCI Kate Daniels series.

Doing another short-short review of this fifth book in the DCI Kate Daniels series.