I feel so glad and so lucky that I found a charming little theatre in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and this play to attend. It was a phenomenal performance and experience all around. This is the best part of traveling: finding gems like this.

First of all, the space and background: let me set the stage, if you will. The Fulton Theatre is a grand, historic old opera house, of a certain type. The main theatre space is opulent, extravagant: ornate carvings, gilt, red velvet. My date and I snuck in to see this space after our play was over; but Next to Normal was performed upstairs, in the “studio.” It reminded me very much of the iDiOm/Sylvia, with spare furnishings and rows of chairs set up on the floor for the audience. I was a little disappointed not to see the big grand theatre in action, of course, but I admit seeing this smaller, simpler space was a comfort, because it reminded me of another theatre I’ve really appreciated (I’m still remembering Clown Bar fondly).

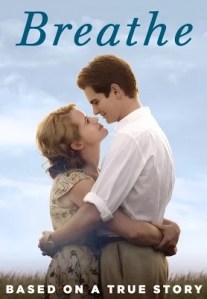

the lovely Fulton Opera House (photo credit)

So, a small space, unassuming, and with moderately minimal props and backdrop, and a small cast of just six. I have seen a larger cast play in small space – Clown Bar was one of those exceptions – but generally a smaller space does mean fewer players. They did indulge in costume changes, though.

Now on to the play, itself.

Next to Normal was written by Brian Yorkey (book and lyrics) and Tom Kitt (music), and I appreciate it very much as a play, to begin with. The topics it deals with are not small undertakings. Family dysfunction and severe mental illness are difficult to approach in any art form, I think. Here we have a mother, Diane, who is ill – how ill becomes gradually clear, but she clearly struggles to get out of bed and deal with her daily life within the home, let alone outside it. Her husband, Dan, means well, but he’s ill-equipped to help his wife with her outsized problems. There are two children who are affected in different ways. And there’s a big reveal part-way through, which I won’t spoil for you here, but it’s important.

Did I mention yet that this play was a musical? A rock musical, that is. It sounded weird coming in (doesn’t it sound weird?) – a rock musical about mental illness and family dysfunction.

The high-school-aged daughter gets her first boyfriend, and Diane has a psychiatrist, and then another (both played by the same actor); and that’s the whole cast: mom, dad, two kids, boyfriend, psych. In two acts, Diane gets sicker. She is prescribed lots of drugs; she experiences hallucinations; she attempts to kill herself; she is hospitalized, and undergoes electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). The nuclear family learns some things about themselves individually, about each other, and about how they work together. The ending is surprisingly hopeful, but feels earned.

My one real concern that I want to voice is something that often concerns me in conversations about mental illness. There seem to be two well-intentioned stories we tell ourselves/each other: that it’s okay to take drugs, to get the help one needs; and that one is stronger if one can be okay without drugs. I think it’s tricky to navigate these two messages, either one of which can be potentially damaging. On the one hand, there’s an argument that we’re too pill-happy in this culture, and that we start our kids on drugs too young. On the other hand, the feeling that you’re stronger if you can “do it” without drugs is really problematic for those people who suffer from conditions that require medication, as some do. The narrative of this play came down a little bit on the side of praising and admiring the drug-free path. And if that works for the fictional Diane, of course I am so happy for her. But that kind of praise can be discouraging, even damaging, for patients who need drugs to be okay. I just wanted to voice that because it occurred to me as I watched the play unfold. And as I’m writing this, I guess I need to observe how personal this material felt. Without violating anyone’s privacy, I thought of some loved ones who have struggled or are currently struggling in ways I recognized here. It was sobering and hard to watch, of course, but it also felt good to have certain people seen. Art is powerful. I’m glad that art addresses such topics as these – even the really hard ones – because the hardest parts of life deserve to have this light shined upon them.

Also, can we talk about the extraordinary image, above? Click through to the larger version. That woman with her blurred-out face, the suburban ideal in her torso, and the pills spilling out from her lower extremities. The sense of time passing all around her. That’s an ideal of accompanying art.

Even with this serious and disturbing material, Next to Normal is remarkably also very funny, and so heartwarming, even through the challenges. And played by such gifted actors – I could feel their passion and power. I paused to admire, at intermission, how odd it is that I can be simultaneously aware that this is “just” a play, and also so invested in these characters who are fiction, and I know that, and yet they make me laugh and cry, and I just want for Diane to be okay and for her daughter Natalie to feel loved and to know it’s okay, she doesn’t have to be perfect to make up for everything… I want Dan to know it’s not his job to fix his wife. Gosh, but I love the theatre.

The thing that was most surprising and impressive about this play I’ve saved for last. Listen to this: the actor who played Dan was unavailable at the last minute, and so they called upon an actor with twenty-four hours’ notice to step in. Jeffrey Coon did not have time to learn his lines; he played the role with a bound script in one hand, flipping through its pages as he went. But he knew the scenes! And he knew the music! He played the physical role perfectly, including interactions with other actors; he knew his blocking. And recall this is a musical: when he glanced down at that playbook for his lines, he was often not speaking but singing them. He knew the songs, musically, just needed the words as he went. Because Dan is some kind of businessman, often carrying a briefcase, he was able to make that bound script often serve as a prop, so that it sometimes disappeared and we could forget about it altogether. I have NEVER seen this before. And I cannot imagine it’s ever done this well: Coon’s acting as Dan was superb, spot-on emotionally and in key with his fellow players. His singing was impressive – great voice, but also timing and feeling. I cannot communicate here how impressed I was with this performance. I didn’t know it could work this well. I can only assume this guy (who works for the Fulton as his day job as well) is a professional ideal. My admiration for this art form has just been raised another ten notches, watching this man slide into this slot so smoothly. During final curtain calls, the other actors made a point to celebrate him, too, so that I could see they shared my feelings about his incredible performance.

I feel again like the luckiest woman alive, when I get to travel through a small city and find a shining experience like this one. I’m going to treasure Next to Normal, the Fulton Theatre, and Jeffrey Coon’s performance for some time.

Filed under: musings | Tagged: family, health/hospitals, mental health & illness, theatre | 3 Comments »