Liz always recommends winners, but this one is the best of the year so far.

Liz always recommends winners, but this one is the best of the year so far.

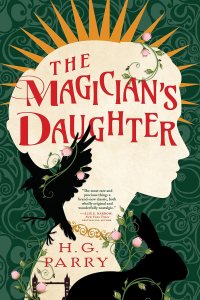

The Magician’s Daughter is a dream of a novel about magic, family, trust, coming of age, a changing world, and figuring out what’s right (or the closest we can come) and what’s wrong. I confess I am in danger of being suggestible by the Alix E. Harrow blurb on the cover of my edition, which reads in part: “a brand-new classic, both wholly original and wonderfully nostalgic.” I read that before I read the book, so there’s a danger there. But I think she got it right: there is both the tried and true and familiar here, and something fresh and new. I loved it so much. And this may be in part the right book at the right time, but I fell into it in ways I needed to.

Biddy has only ever known life on the island of Hy-Brasil, where she lives with her surrogate father figure, a mage named Rowen, and his familiar Hutchincroft, who sometimes takes human form but mostly lives as a golden-colored rabbit. She is now about sixteen, or seventeen: they can’t be sure, of course. She’s always known the story, that she was found shipwrecked alone in a small boat, which had been very unusually allowed to drift near Hy-Brasil. Off the coast of Ireland, beyond the Aran Islands, the magical island is only detectible every seven years; to accept the small craft that bought her there as an infant has always meant to Biddy (in her secret thoughts) that there must be something special about her. She might not have magic as Rowan does, but she hoped she was meant for big things.

And so in her teenaged years, it has begun to chafe that Rowan won’t let her leave the island. And he’s been leaving himself, more and more, in his form as a raven, out all night and sometimes even returning hurt. The outside world seems to be unraveling in some way, and Biddy is ill equipped to understand or help, being without magic and forbidden and unable to travel, but change is afoot…

Eventually Biddy and the reader learn that magic has been slowly leaving the world. The British Council of mages has seen upheavals in the last seventy years (mages live a long time, and this is all easily within Rowan’s experience), and those in power just now are not necessarily doing the kind of good work Rowan (and Biddy) believe in. It is now the year 1912, and Biddy is ready to step off her island for the first time in her memory, to take some serious risks. On the streets of London, she sees poverty and exploitation as well as overwhelming numbers of people (and intriguing fashion, which she’s always been curious about). She meets some looming figures from Rowan’s past, and the character of her beloved guardian gets somewhat complicated by these new perspectives. Especially in the Rookwood Asylum for Destitute Girls, she sees suffering and injustice like she’d never comprehended. There is much wrong in this larger world, and even all the magic one could dream of couldn’t fix it all, but with magic leaving the world things are worse than they should be. What can an orphan girl with no magic of her own possibly do? But with Rowan in profound danger, Biddy will have to try.

There is a touch of the fairy tale here, a dose of historical fiction, and lots of magical fantasy elements. Parry excels at world-building and realism. I love the sense that this could all be real, that there could be little hints and strains of magic in this real world that we regular folk are just not accustomed to noticing. Mages, like the rest of us, are susceptible to jealousies and the corruptions of power. There is a strong hint at the end that the world is about to see some larger problems – and again, this is 1912, so that is very believable foreshadowing. I desperately want the sequel to this lovely, absorbing novel! And will be investigating Parry’s backlist.

I needed the escape offered by this novel at this precise time that I picked it up, and am calling it the best book I’ve read this year. Thank you again and always, Liz. (I’m typing this review on your birthday although it won’t publish for some weeks.) Hugs and magic.

Filed under: book reviews | Tagged: family, fantasy, historical fiction | 4 Comments »